Women play key roles in commercial fishing and fishing communities, and we’re sharing a few of their stories, including what drew them to the profession, what term they prefer to be called (fisherwoman? Fisherman? Fisherperson? Fisher?!), the sustainability interwoven into their work, and why they keep returning to the sea year after year.

A Fisherwoman Connects with Her Community

Photo courtesy of Slack Tide Fisheries

Elisa Brackenhofer is a fisherwoman and co-owner of Slack Tide Fisheries, based out of Bellingham WA. The Slack Tide Fisheries mission is simple: wild, local, sustainable seafood for local people, direct from your fisherpeople.

Elisa and her husband, Jace, started Slack Tide out of a desire to connect folks in their community with sustainably caught seafood, helping them understand just how fish gets from the sea to their plates. “My now-husband and I fished together when we were younger, and I eventually went up to Bristol Bay [Alaska] as well to start my own fishing career. We founded Slack Tide in 2018 because we wanted to bring local salmon to local people.”

In the last six years, they’ve done just that. “Being able to connect with this community has been the most rewarding part,” Elisa explains. “We get to be stewards for the water and understand what’s happening. We work with government agencies, nonprofits, and restaurants and get to connect with all kinds of different communities.”

Those communities have responded enthusiastically to the high-quality seafood that Slack Tide catches and sells. That’s why Elisa is passionate about representing the level of care and stewardship that goes into fishing. “I wish more people knew the amount of work that goes into just one piece of salmon on your plate. It’s just like being a farmer. You see one potato, but you don’t see what it takes to grow that potato. There’s also a big misconception that fishermen don’t have the ocean’s best interests in mind. It’s actually the opposite. Our livelihoods depend on a healthy ocean.”

When asked what term she prefers to go by, Elisa shares, “It’s kind of a fun thing to say ‘fisherwoman’, since it’s traditionally ‘fisherman’. I don’t take offense to being called a fisherman, though. I’m not picky, but it is nice to be recognized that you’re not a man.”

Photo courtesy of Slack Tide Fisheries

A Lifelong Passion for Salmon and Sustainability

Photo courtesy of Duna Fisheries

Amy Grondin, of Duna Fisheries, is based out of Port Townsend. As she recalls, “Getting into fishing was a happy accident in my early twenties. I was living and skiing in Jackson, Wyoming. In Jackson, there are two seasons – the summer that’s about hiking and fishing, and the winter that’s based around skiing. If you lived there and worked in the service industry, you had two jobs, one for summer and one for winter. I hadn’t found my summer job. I got a call from a friend who needed a deckhand, someone had quit on short notice. I was young and looking for adventure. I went to Alaska for one season and got hooked.”

Fast forward thirty years, and Amy and her husband Greg are a company of two, fishing in Washington from May to mid-June and heading to Alaska after that for July through September. She explains, “We use a hook and line type gear. It’s a sustainable way to fish in that if we catch a fish that isn’t our target species, we can release it and there’s a very good chance it will swim away and live to complete its spawning process.”

Decades in the fishing business have given Amy unique insight into the role that humans play in their foodshed – whether that be at sea or on land. “There isn’t a way that we produce land food or seafood that is 100% sustainable,” she explains. “There’s no way around the fact that we [human beings] are apex predators. Because we eat, we have an impact. Fishermen are often held to higher levels of sustainability than anyone producing food on land. The salmon fishing industry tends to be quite sustainable. We target our catch where they’re at in their life cycle, and our fishing gear relates to that stage of the life cycle. For example, we use hook and line gear because we’re fishing on the ocean, and at a time in salmon’s life cycle when they are feeding and will take a hook. Fishermen who use gillnets work the waters they know to be traveled by salmon on their way from the ocean and towards rivers. Purse Seiners set their nets right up near the shore where salmon are schooling up, pretty much not feeding, and using their fat (stored energy) to swim for their natal streams to spawn.”

Photo courtesy of Duna Fisheries

Photo courtesy of Duna Fisheries

Amy is passionate about sharing her knowledge and lived experience on the water with those who seek to steward the seas that nourish both her livelihood and the places she loves. “I wish more people knew that fishermen, in particular salmon fishermen, are very concerned about species survival and the return of salmon to their streams. Salmon fishing in the US is highly regulated. Every year there is a months long a process participated in by the US and Canada; Tribal Co-Managers; the coastal States with salmon fisheries; scientists and nonprofits along with fishermen and other stakeholders to evaluate the health of salmon populations and decide how many fish we are allowed to catch. There’s not a salmon fisherman I know that wants to catch the last fish in the ocean as it’s their annual returns that assure us jobs that feed people.”

That’s why, in the off-season, Amy spends her time talking to elected officials about salmon issues, planting trees and cleaning beaches to restore habitat, and collaborating with commercial fishermen and research scientists to build trust and reach their common goal of healthy salmon returns. “When you get fishermen and marine researchers trusting each other and working together, you get amazing real-time solutions you couldn’t get from one group working alone.”

Fishing is hard work, but work that Amy finds deeply rewarding. “I love the lifestyle of living on a boat,” she shares. “It’s never the same day-to-day to hour to year. Sometimes you’re just paying for the groceries, and sometimes you have a really good catch year that makes up for it. The work I do on the other side [off-season] is rewarding in that I’m giving back to the resource I’m taking from. And, of course, the food that is created is like nothing else.”

As for terminology, Amy calls herself a fisherman. “I think that’s my generation,” she explains. “I stand on the shoulders of Amazons, women before me working really hard to be on the water with men, to own their own vessels and companies, women that grew up in the 60s-80s. They wanted to be ‘fisherwomen’ as they earned it, to let it be known that they worked as hard or harder than the men they fish beside. Because of that, now I can be called a ‘fisherman’, and not feel the need to differentiate.”

Amy adds with a laugh, “I guess we could use fisher, to be neutral, but they’re such a cranky, vicious animal!”

Finding Seafood Year-Round

Photo courtesy of WA Sea Grant

Jenna Keeton is a Fisheries Specialist with Washington Sea Grant, a federal– university partnership between NOAA and the University of Washington that provides support to marine ecosystem users – including commercial fishermen and fisherwomen like Elisa and Amy.

Jenna shares, “Our fisheries team follow the journey of the fish or seafood product from the water to the plate. My specialty comes when the product is ready to eat – getting it on a plate, getting folks to understand where their seafood comes from and whether it’s harvested sustainably.”

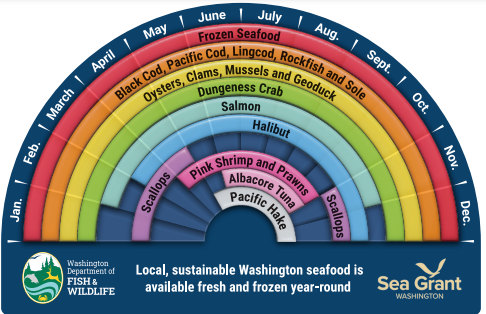

Jenna supports seafood harvesters as they market their catch, helping consumers identify which seafood is sustainably caught – and why it matters. “Most people don’t know that in Washington, we have seafood available year-round with a wide variety of fisheries like pink shrimp, albacore tuna and sablefish, among others. We have so many options.”

Jenna is especially passionate about informing consumers about the many options they have, including some they may not expect. “Frozen seafood is a really good, high-quality option. Freezer technology has improved so much over the last 30 years. People should feel confident and comfortable buying a frozen filet.”

She wants folks to feel like they have options when it comes to both price and convenience; the ultimate goal is just more people eating more sustainable seafood. “When you’re buying seafood in the store, try to look for labels that say ‘caught in the United States’,” she explains. “We have extremely rigorous sustainability regulations in the US. Of course, a dockside market or a farmers market are a little more work for the consumer to reach, but it shortens the supply chain so the fishermen get more of your dollars.”

And while it’s important that seafood harvesters get the money they deserve, Jenna knows just how important it is that they receive appreciation from their community and consumers. “When I was a deckhand, it was clear that we could be better as a state at knowing our fishermen. It’s such a noble profession, just like farming. We should try to meet and thank anyone who produces food.”

Photo courtesy of WA Sea Grant

While being a fisherwoman is now becoming a respected and recognized position, women in the world of commercial fishing is not a recent trend. The many fisherwomen who came before paved the way with their strength, drive, and expertise. While conditions have dramatically improved, there are still barriers as a woman in this industry. If you’re curious about this world, step in, find a mentor, and more space will be made for all.